*The names of persons cited in the article have been changed

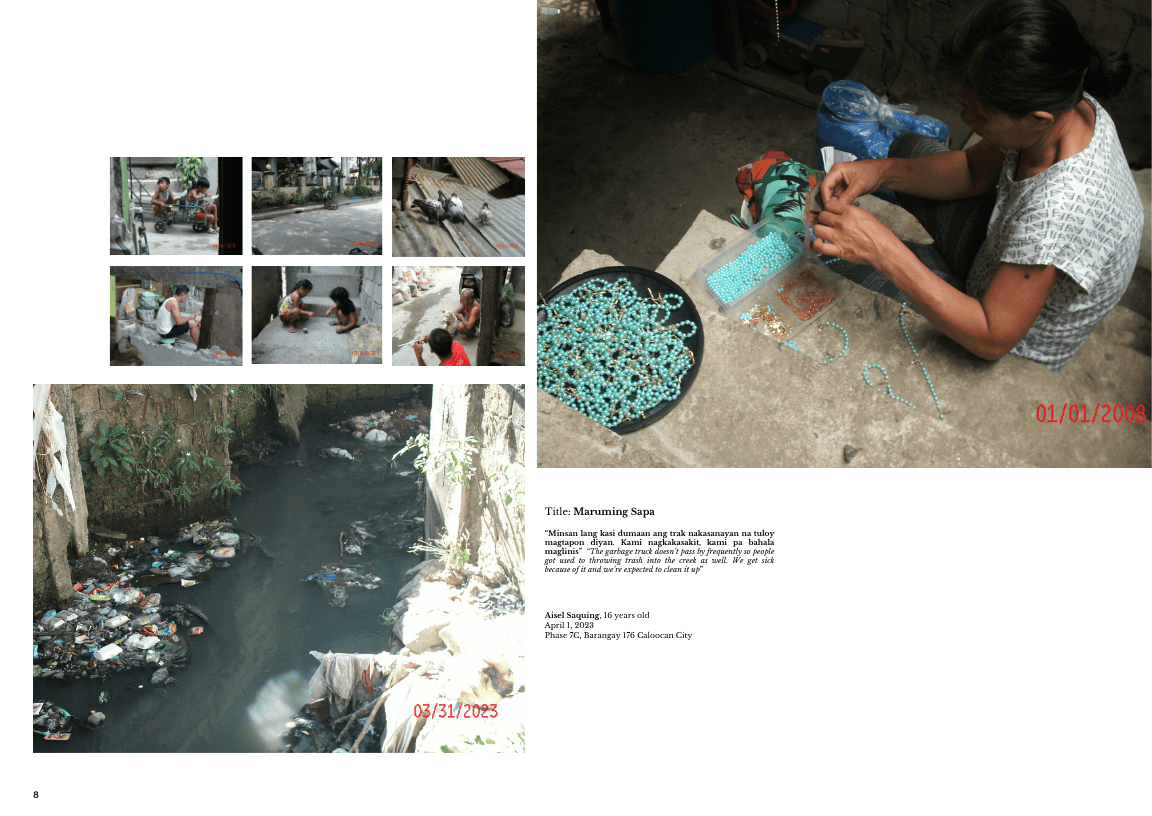

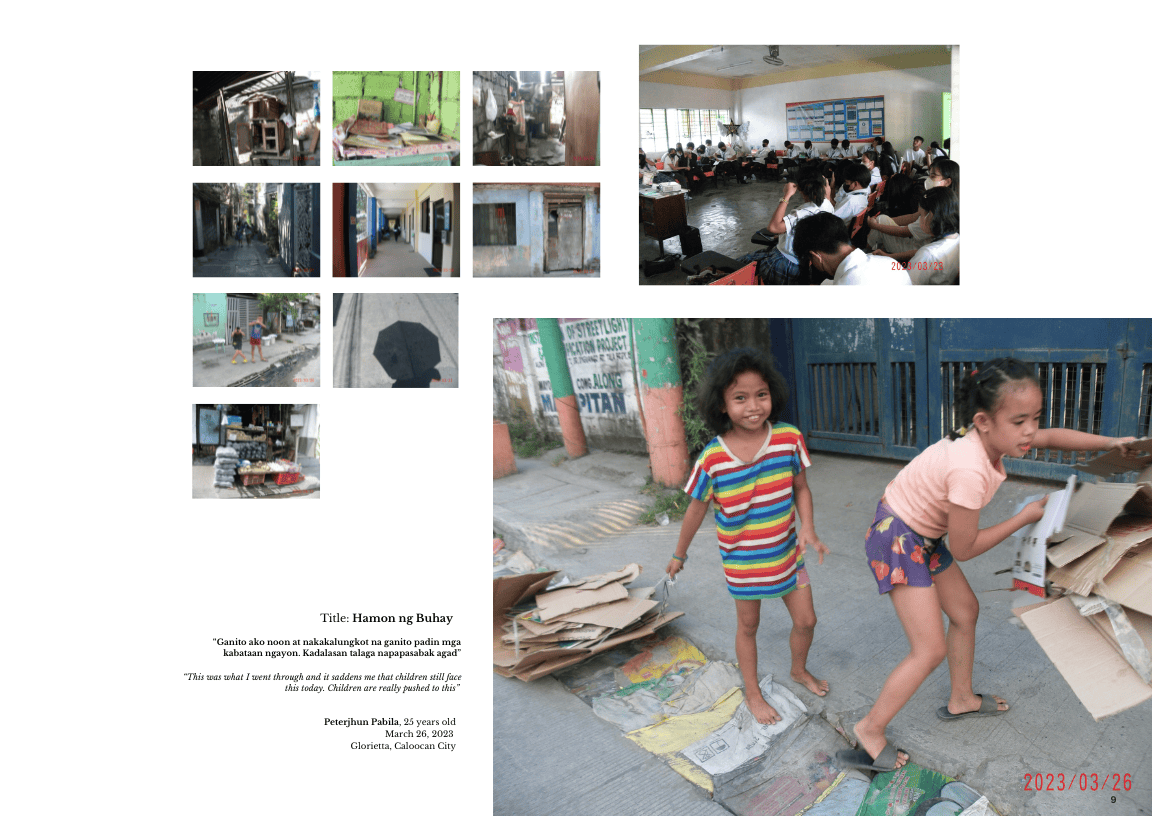

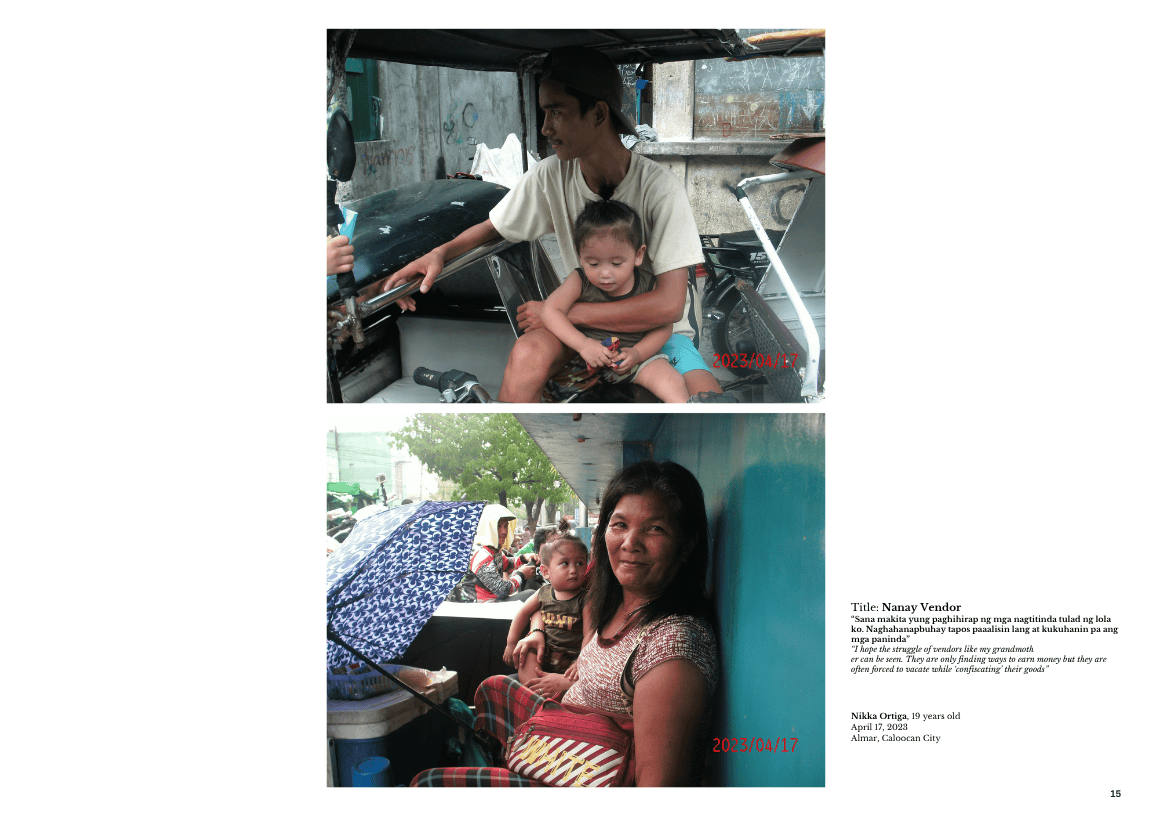

Those who say that the young people in the poor neighbourhoods in Bagong Silang are lazy or good for nothing have not known the depths of the experience of young persons like Bren. At the age of 10, he has already trodden the streets of Manila with his father selling pails and wash bins to make ends meet. While other kids his age are supposed to be hanging out with friends or spending time at school, he has already learned to endure the heat and hunger to earn a living. The eldest in a brood of five, he detested the way others looked down upon him and his family. Growing up in life of deprivation, he believes that being poor does not make someone a lesser person. He felt bad that nobody would give them respect anymore. His longing to get himself out of that hard life has consumed his young mind. He eventually learned to be tough, believing that to survive, one must fend for oneself and claw back at those who judge and condemn those who were unlucky enough to be living on the margins.

“There are many nasty people in our community,” Bren said expressing his frustration on the people who have discriminated against him. “I felt like growing up in a jungle; to subsist I taught myself not to put my trust on anyone easily. I need to do things my way or perish,” he added.

When Bren got older, he got tired of following his father. He resented that people would always tell him what to do. His rebellious feelings fractured his relationships with his parents. He eventually found comfort in the company of his peers and spent more time with them. They constituted the Bulabog Boys, a gang of tumultuous youth who earned the ire of neighbours for staying late in the streets, getting drunk, starting fights with rival gangs, and getting into trouble with local authorities. He got particularly close to one of his peers, Rexie, whom he regards as a younger brother. They were inseparable and watched each other’s backs. In 2019, both of them were picked up by tanods or community law enforcers following a report of robbery in another locality.

‘The authorities did not care that we were young. They simply treated us like drug lords,” Rexie, who was 16 years old then, recalled. “The tanods dragged us out of our house and forced us inside a vehicle. They threatened to harm us and brought us in a narrow holding cell. We were not fed properly. Our parents were not able to see us right away. We were released after three days with no charges filed against us. They took us for being the ‘usual suspects’ because of our reputation,” Rexie lamented.

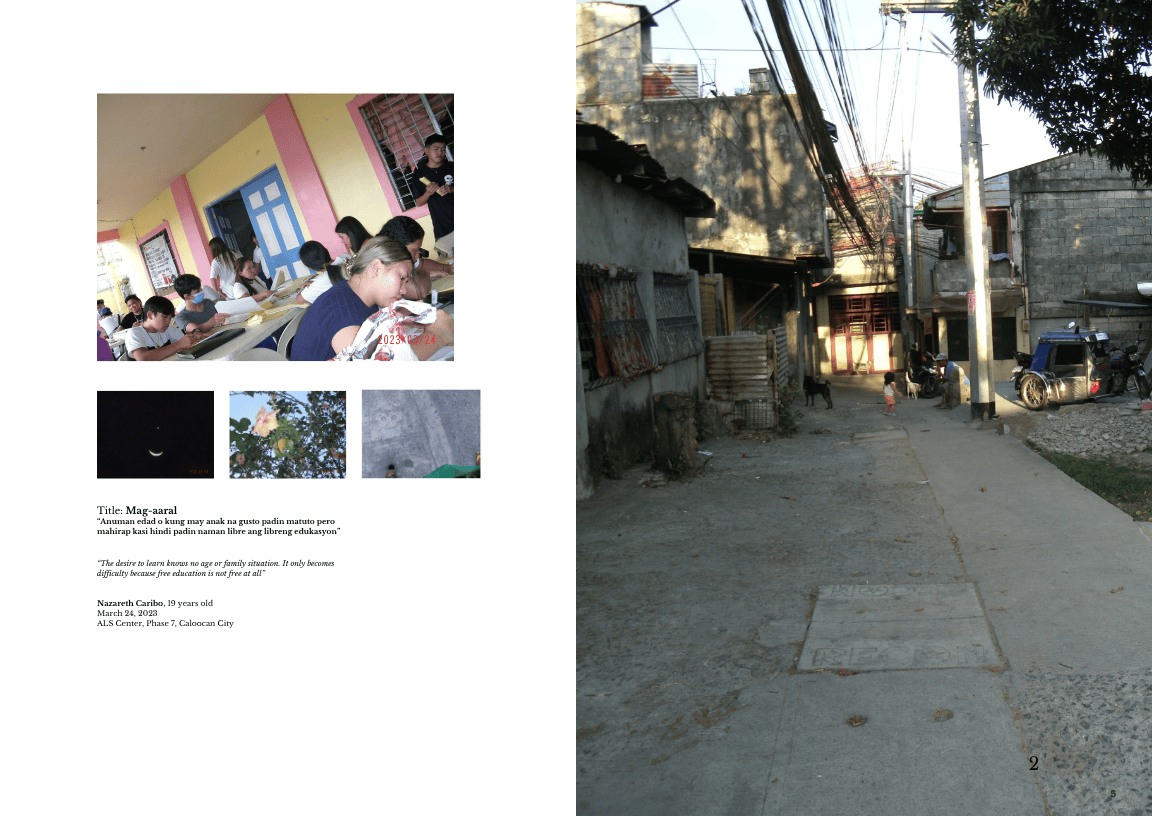

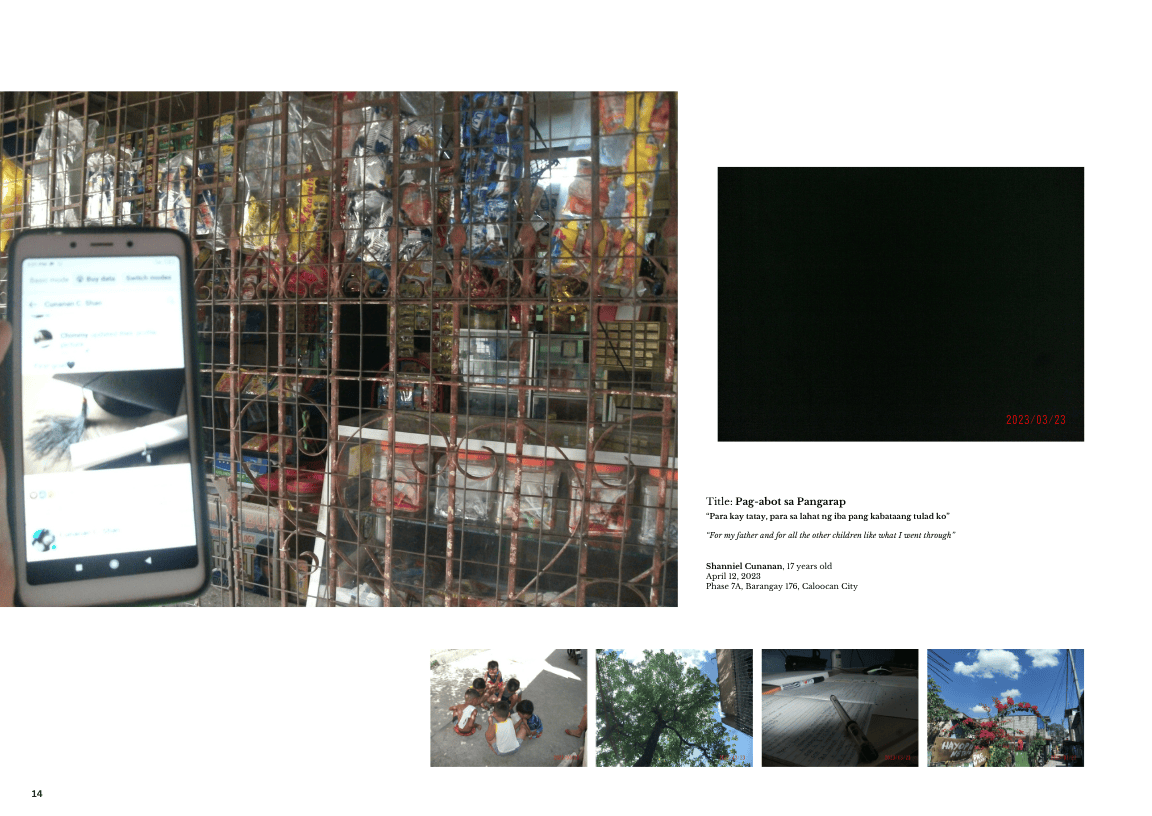

The travails of Bren and Rexie are not uncommon for impoverished youth in Bagong Silang, a relocation site for evicted informal settlers in Manila. Records from the Barangay Council for the Protection of Children (BCPC) show that more than 500 young people have been apprehended by authorities in Bagong Silang in 2019.The neglect, discrimination, and abuse suffered by these young people prompted the establishment of the project ‘Following the Child.” The EU-supported project seeks to strengthen the protection of children at risk and children in conflict with the law through community-based interventions and partnerships with local authorities in the juvenile justice and social welfare system. It is implemented by Balay Rehabilitation Center and Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center (CLRDC) together with DIGNITY.

Under the Juvenile Justice Welfare Act (JJWA) persons below 18 years old who are accused of a certain offense must not be regarded as common criminals nor be subjected to ill-treatment or torture. Their parents must be informed about their situation right immediately as well and they must be turned over to the BCPC for documentation and assessment. The local social welfare office, under the juvenile justice pathway, is tasked to subsequently sign them up to intervention or diversion programs such as counseling support, learning and skills development.

The proponents of the Following the Child Project have eventually persuaded the public officials in Bagong Silang to establish a Diversion Committee and to strengthen the programs of the BCPC in order to secure the young people from harm and protect them from violence. The have also offered seminars on handling children in conflict with the law without using excessive and inappropriate force.

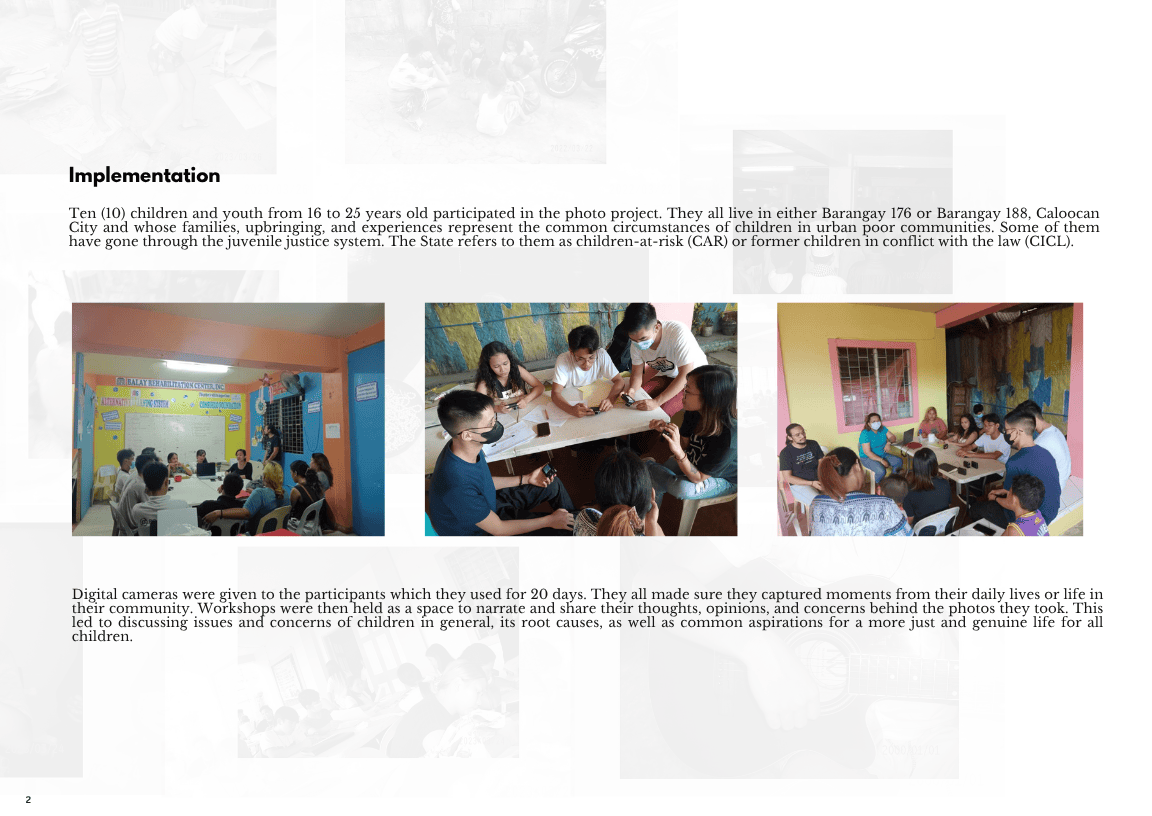

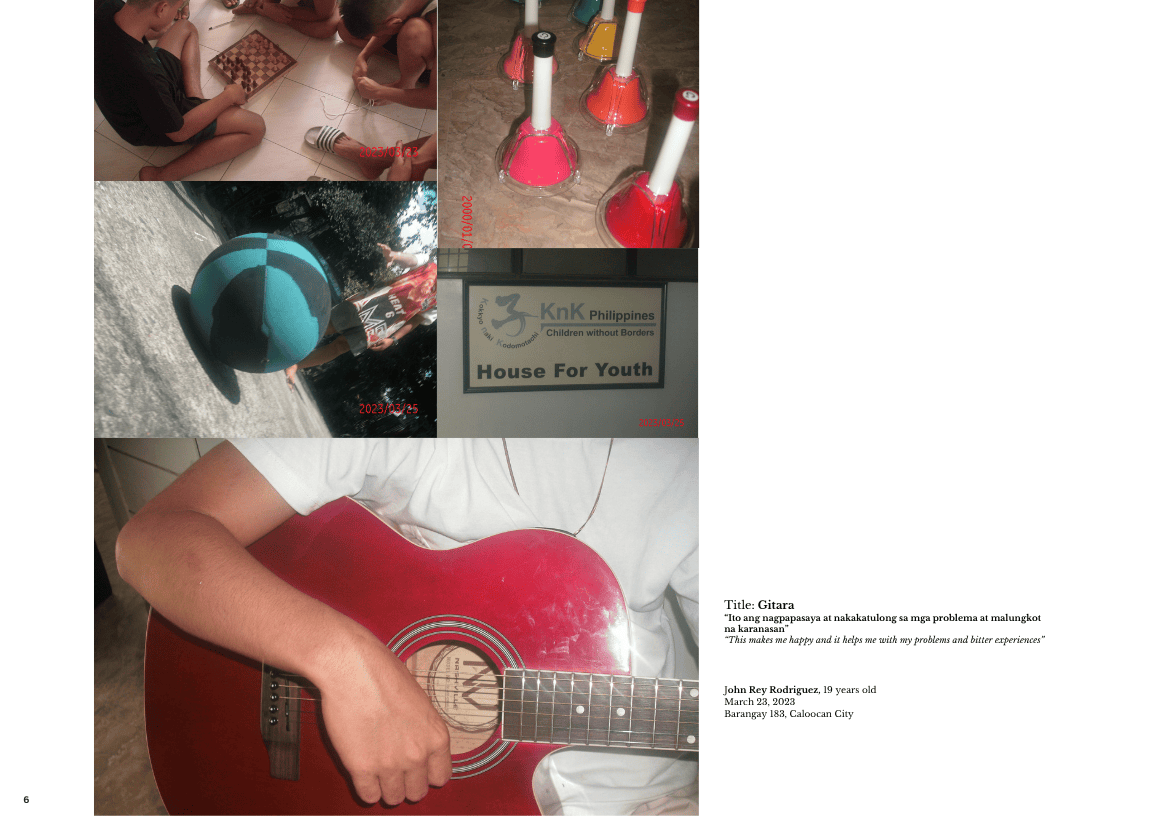

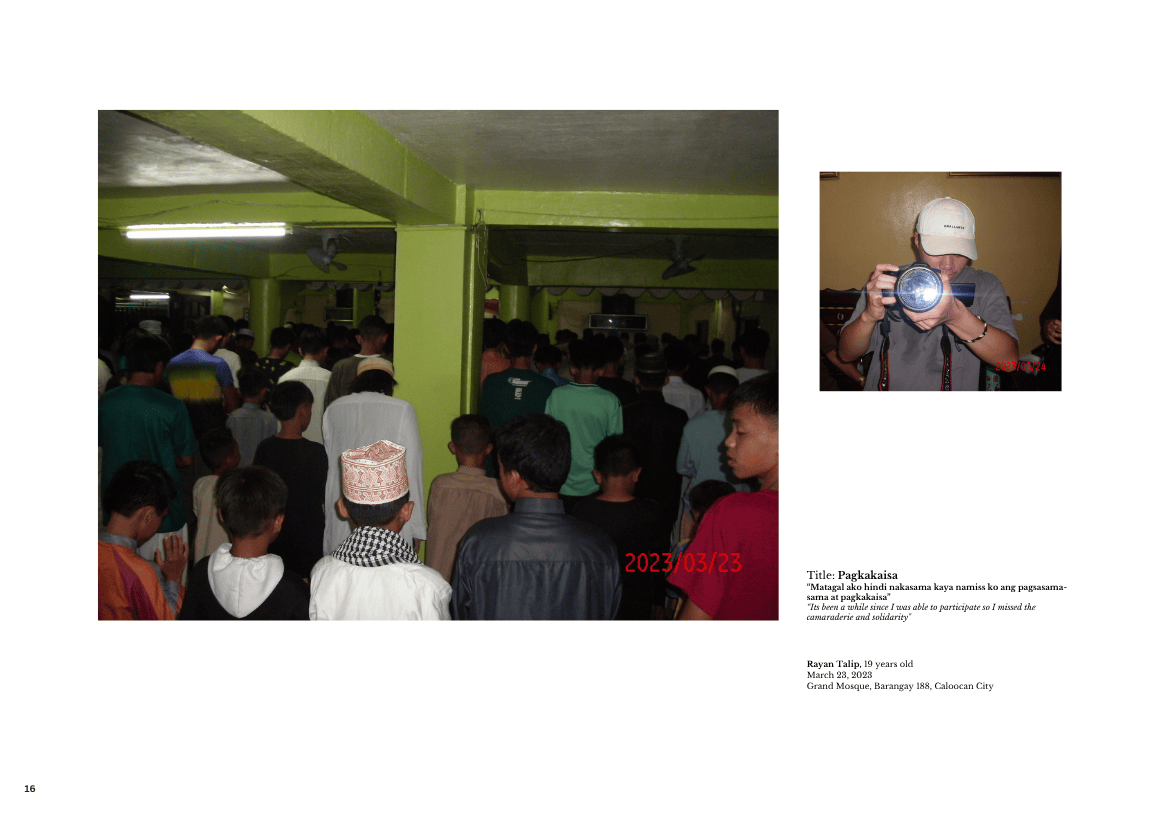

Through the project, both Bren and Rexie joined other similarly situated young people in Bagong Silang in activities where they could share and learn from their experiences and gain new knowledge on how to develop their creative and productive potentials. They attended seminars on children’s rights and workshops on the future, so-called visioning, to rekindle their hopes and aspirations. They attended study sessions on the role of young people as social actors and joined an assembly to strengthen the organization of youth at risk.

During a workshop on children’s rights, Bren said that he got into thinking aboutthe distinction between a human being and “being human.” “It is one thing to be born, but it is another thing to realize one’s value as a human being,” he pointed out.

‘I lost my respect forother people because of what I went through. So, in turn, I learned to distrust and resist them. But now, I try to understand where they are coming from and at the same time acknowledge my worth bilangtao – as a person. I wanted to recover and give back the respect that I lost,” Bren said.

The project also invited the parents of the Bulabog Boys to seminars on how parenting could be a way to promote self-worth and respect for children. The parents realized that nurturing sound relationships with their children could strengthen the sense of protection among young people and reduce the risk of their engagements in activities that can put them in harm’s way.

“It feels good to be listened to, and not to be judged by anyone,” according to Rexie. ‘We may be young, but we deserve to be given attention. After all, we also have things to say and capabilities that we can put to good use,” he added.

Rexie is now 18 years old. In between his studies in the alternative learning (ALS) system program managed by Balay, he drives a tricycle to help his mother. Other members of the Bulabog Boys also attend the class.

At present, Bren works as a service crew in a food shop. He has already completed his ALS education and is saving to pursue a degree as a teacher someday. He is now 20 years old. When asked what he wanted to say to his former gang members, he said: “Panatiliingbataangpuso, peromaunladangpag-iisip.” (Let us keep our hearts young, and let our minds grow).